- Categories:

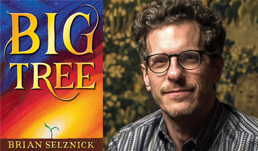

A Q&A with Brian Selznick, Author of May/June Kids’ Indie Next List Top Pick “Big Tree”

- By Zoe Perzo

Independent booksellers across the country have chosen Brian Selznick’s Big Tree (Scholastic) as their top pick for the May/June 2023 Kids’ Indie Next List.

Big Tree follows two young Sycamore seeds, Merwin and Louise, as they search for a safe place to grow in the Cretaceous era.

“Through exquisite art and spacious language, Big Tree is told by sibling sycamore seeds making their way in the world. It is captivating, empowering, and impactful; written for a young audience and to be enjoyed by all,” said Meghan Bousquet of Titcomb’s Bookshop in East Sandwich, Massachusetts.

Here, Selznick discusses his process with Bookselling This Week.

Bookselling This Week: I’m going to date both of us here, but I read The Invention of Hugo Cabret as a kid when it first came out. And I remember the sense of wonder at this distinct format and how immersive it was. Reading your work as an adult, the experience is no less impressive. But I have to ask, what does your process look like and how long does it take to complete a story like this?

Brian Selznick: It generally takes anywhere from three to five years to make one of these books. Hugo, Wonderstruck, and The Marvels each took three years. Big Tree, for various reasons, took five years. A lot of the time is spent simply trying to figure out what the narrative is. I see things visually, but when I’m putting together a story it doesn’t come to me in any kind of order. I often will begin with something that ends up being later in the story. But there’s a kernel of an idea that is interesting to me, enough to want to keep exploring. Later, I start putting the narrative into an order that begins to make sense.

I usually start off with a place or a single general idea, and then think about a character who would appear in that place and who would connect some of the thoughts that I’ve had. The last part of the process is figuring out the emotional reason that the character is being driven to make these choices and to do these things in the world that I’m creating. It’s a somewhat backwards process because ultimately, the emotional reasoning for everything is the most important.

I think most people think they have to write in order. And because they don’t know how something starts, they think they can’t begin or they shouldn’t begin. It took me a long time to recognize that it’s okay to work in whatever way you work, as long as you work. I can sit down and just write the scene that I’m seeing, and that’s a beginning. John Cage the musician is quoted as saying “start anywhere,” and I think that’s a very, very good piece of advice to follow.

BTW: Working on this project, you gave yourself extra limitations. Everything needed to be based in science, and your personification of the seeds (and other characters) is limited to actions they could feasibly perform. What drove you to embrace these extra challenges, and how do you think it ultimately enhanced the finished story?

BS: I generally believe that limitations are helpful, and having boundaries is a good thing. The genesis for this story was unusual for me (and for most books), because it started as an idea for a movie from Steven Spielberg. He asked me to write a story about nature from nature’s point of view. I have to admit, I didn’t actually think it was possible when we first began. Especially because he’d originally imagined the story taking place during the Devonian era, before the dinosaurs were around and there was very little biodiversity.

I eventually suggested that we move this story a few 100 million years later to the end of the Cretaceous era, right before the asteroid hits the planet and kills most life on Earth. That seemed like a good metaphor for the existential threat the climate is facing right now. By the end of the Cretaceous era, most of the forests had full biodiversity and looked very much like our forests today. I thought it would be important for the world of the story to have a direct relationship to the world that we are in today, so the viewer could leave the movie theater into a world that they had connected with.

There was one thing that wasn’t going to be based in science. The animators were trying to figure out where to put a face on the seeds, because none of us could imagine making a film with characters who have no faces. But when the pandemic hit, it became clear that the movie was never going to happen. I proposed that I take the story I had created for the screenplay, and make it into a book. That’s when I realized I should make the rule about science apply to the pictures as well. The reason the faces never looked right on the seeds was simply because seeds don’t have faces.

I realized I was going to have to make a 600-page book with main characters who have no faces. But the thing I like most about books is the way I can work with the words and the pictures together. In a successful picture book, the words need the pictures and the pictures need the words so that they create a third thing. The ways in which the pictures and the words are dependent on each other helped me when I was working on Big Tree.

BTW: My favorite panel in the entire book is a shot of the Earth and the newly created Moon. It’s part of a sequence portraying the Big Bang and evolution of life on Earth. And it emphasizes how much research you put into this book. The end matter describes you connecting with paleobotanists and experts at the Smithsonian. Can you talk a little more about the research and anything exciting you learned along the way?

BS: All of it was pretty new to me. I knew a little bit about the mycorrhizal system, which is the fungi that live beneath the soil in forests that connect the roots of trees, turning them from individual trees into a real community. I had listened to an episode of Radiolab called “From Tree to Shining Tree” about Dr. Suzanne Simard, who really made this connection with the mycorrhizal system and the ways in which they get information to and from trees around the forest. The first paleobotanist I reached out to was James Boyer at the New York Botanical Garden. He is the one who first told me about the idea of fossil species, and that by the end of the Cretaceous period there was full biodiversity.

I eventually met a scientist at the Museum of Natural History who studies foraminifera. They are nearly microscopic creatures, neither plants nor animals, that have shells and fill the oceans. When they die, and their tiny shells fossilize, they capture the carbon from the atmosphere. When scientists date these tiny fossils, they can measure the carbon dioxide that was in the air at the time. It’s because of foraminifera that we even know what climate change is. I thought, “Oh, I have to put that in the book somehow.” And because the book is from the point of view of nature, I wanted to find a way to give them some human attributes that would make sense for the work that the foraminifera have been doing in real life.

I created these characters called the Scientists, who are these tiny creatures in the water that Merwin and Louise meet when they’re trapped in a shell by a crazy piece of seaweed. The Scientists in my story are working to write down all of the information about the world around them. They inscribe that information in their bodies with the very clear idea that one day someone will be able to read their mysterious writing and understand. And, of course, we are the people that they are dreaming about in the future.

BTW: We see some very timely messages in Big Tree, like the beauty of nature and the importance of hope. One of the big ones being that no matter how small someone is “there is always something you can do.” And that through community, many small things can make a big difference. Can you talk a little about your connection to these messages, and how you decided to incorporate them?

BS: I’ve always felt very proud of the fact that my audience is mostly children. They’re the best audience in the world. They’re very direct, very clear, and very passionate about what they love and don’t love. But when I’m actually writing a book, I’m not really thinking about the audience. I’m thinking about myself and what I need to do to help myself feel better, to get through the day, to explore things that I’m curious about.

The characters I think of are generally children, so it makes sense that most of the audience who connect with the story are children themselves. But I have always written about things that are not generally considered topics kids would be interested in, like French silent films, or the history of Deaf culture, or where museums came from. A lot of the science in Big Tree is the kind of science that you may learn in graduate school, or you may discover as an adult later in life, but these were all parts of the story that were interesting and fascinating to me.

At the beginning of the pandemic, I got stuck on one side of the country, and my husband got stuck on the other. We didn’t know when we were going to see each other again, and it took me a while to be able to do anything because I ended up feeling paralyzed. Now, I live in New York so I can essentially see right into everyone else’s apartments, and a kid put a sign in the window across the street that said “let’s make art.” That got me off the couch and starting to work again.

When I was ready to start thinking about books again, I realized I wanted to tell the story of Big Tree. Merwin and Louise are powerless and tiny, and yet they figure out a way to find someplace that’s relatively safe for themselves. When they are thinking about saving the world, it’s not only for themselves, it’s about all future life on the planet. So at the very end of Big Tree, there’s a 66-million-year time jump, where we get a little glimpse of what the future looks like. It gave me a chance to say, “this is the future that Merwin and Louise are dreaming about,” and we still have to be thinking about everything that comes after us.

In the end, it was really about helping myself feel a little bit better. I figured I’m not experiencing anything unique. What I’m feeling and experiencing is what everyone is. If this is helping me feel a little bit better, maybe it could help other people feel a little bit better too.

BTW: Not only does your book tour include stops at independent bookstores, but you were an independent bookseller yourself! Can you talk about the role independent bookstores have had in your life?

BS: I identify very, very closely with independent booksellers. I identify myself as an independent bookseller, still to this day. I worked at Eeyore’s Books for Children after I graduated from college. I didn’t want to be a children’s book illustrator when I was in school, so Eeyore’s Books for Children was my education. My manager Steve Geck would send me home every day with bags of books to read so I would understand the history of children’s books. I met young people who I would get to know and I’d be able to recommend specific books just for them.

Independent booksellers are the people on the ground, like librarians, who are getting the books into the hands of the readers. I think part of the reason that so many independent bookstores are thriving right now is because they have a very strong connection to their local community. They know who their customers are, who the readers are, who the kids are. They know the teachers, and the librarians, and everyone in town. My time as an independent bookseller put me in that position on the ground, connecting the reader with the book, seeing what would happen when the right book got into the right hand.

That connection with independent bookstores is very, very strong in me and I always feel at home when I go into any independent bookstore. I’m really thrilled that I am able to visit so many as I’m heading out on this tour. Most of them I have been to many times before, but there are so many new independent bookstores that I’m visiting as well. No matter how big the store is, or no matter where it’s located, I always feel right at home and I know that the people who work there are our family.

BTW: Is there anything else you would like to share?

BS: There are so many different ways that we can experience books now. Some people like to read their books on e-readers, there’s an e-version of Big Tree. Some people like to read via audiobook, and there’s an amazing audio book of Big Tree with Meryl Streep narrating, beautiful sound effects, and new text that replaces the pictures. I’m excited that there’s all these different ways in which the story can be told. But ultimately, my favorite way is as the physical book, which is on a shelf waiting in an independent bookstore for someone to come in and find it.