- Categories:

Indies Introduce Q&A with Nico Lang

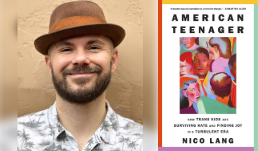

Nico Lang is the author of American Teenager: How Trans Kids Are Surviving Hate and Finding Joy in a Turbulent Era, a Summer/Fall 2024 Indies Introduce adult selection and October 2024 Indie Next List pick.

Kristin Saner of Fables Books in Goshen, Indiana, served on the panel that selected Lang’s debut for Indies Introduce.

She said of the book, “Nico Lang provides needed insight into the lives of trans teens. Following eight trans and nonbinary teenagers, American Teenager shows us that there is no one way to look or be trans — or a teen. We also see that at their heart, these trans teens dream of what’s after high school, gossip, dread tests and class assignments, and try to figure out life.”

Lang sat down with Saner to discuss their debut title.

This is a transcript of their discussion. You can listen to the interview on the ABA podcast, BookED.

Kristin Saner: My name is Kristen Saner. I am co-owner of Fables Books in Goshen, Indiana, and I have the delight to be here interviewing Nico Lang.

Nico is a nonbinary award-winning journalist with over a decade of experience covering the transgender community’s fight for equality. Their work has appeared in major publications, including Rolling Stone, Esquire, The New York Times, Vox, The Wall Street Journal, and many others. Lang is the creator of Queer News Daily and previously served as the deputy editor for Out magazine, the news editor for Them, the LGBTQ+ correspondent for VICE, and the editor and cofounder of the literary journal In Our Words. Their industry-leading contributions to queer media have resulted in a GLAAD Media Award and 10 awards from the National Association of LGBTQ Journalists (NLGJA). Lang is also the first-ever recipient of the Visibility Award from the Transgender Legal Defense and Education Fund (TLDEF), an honor created to recognize their impactful contributions to reporting on the lives of LGBTQ+ people.

Welcome, Nico, I am so excited to talk to you about American Teenager.

American Teenager follows eight trans and nonbinary teenagers. You get to follow their daily lives, get to meet them, and get to know them and their families. My first question is: in today's world, where there are so many legislations that are working against trans people, what motivated you to interview these teens and share their stories? As a nonbinary person yourself, these are probably very close to your heart, but beyond the personal. What was the motivation for these interviews?

Nico Lang: First, I want to apologize to all the listeners who had to listen to my entire bio. If I knew the whole thing was going to be read, I would have cut that down. That was brutal. So, I'm so sorry.

I don't talk about my own identity very much, because I think the focus should be on the kids. But for you, I do want to talk a little bit about the personal stuff. I came out as nonbinary during the pandemic — or sort of re-came out, I'd actually come out a long time ago back when the term everybody was using was genderqueer. I always hated that term. I liked what it signified, but there was something about the actual wording that just didn't jive with me. But it did express a certain thing that I felt about my gender, which was that rather than being masculine or feminine, I've always just felt like a bunch of nothing. And I love being a bunch of nothing. It's great.

I imposter syndromed myself out of it for a long time. Like, “Well, am I really that genderqueer or nonbinary? Do I really deserve to occupy the space?” It took a long time for me to be willing to take up space and to realize that I deserved the space the same way that other people do. It took literally 10 years for me to be like, “All right, I'm good. I deserve this space,” and that was during the pandemic when I was reporting on so many anti-trans bills.

I was having a hard time psychologically covering all of that at the same time, and it felt sort of important for me to declare why. That this is something that I'd been, not struggling with, but trying to negotiate in my mind for a long time. Even if it still felt messy to me, it felt important to say to people, “Hey, I'm a nonbinary person. This is who I've been for a long time.”

It felt really good to place the personal at the center of all of it. And that's what I wanted to do for these kids. You see all of these bills being introduced across the country, trying to strip away basic protections for them — the ability to access the bathroom, to use their correct names in school, to get medical care that meets their specific needs. And they've been iced out of these discussions. Their opinions aren't thought of as being important to decisions that affect their lives, and rather than talking about them in this weird, abstract way, I wanted a project that recentered and said, “Your lives are what matter most.”

You know we talk about legislation, and we talk about healthcare, but those things felt less important to me than really stressing people's humanity. We just don't recognize that these are kids, and they don't deserve to be used as a political football. They deserve to be heard, and respected, and affirmed, and loved for who they are.

I just wanted to explain that these kids are humans and they are people. And it's really sad that I have to do that in 2024.

KS: Well, it certainly comes across. Actually, I find it interesting, it sort of goes back to your struggle with the genderqueer label. Labels are so personal, and we tend to slap them on a group of people and use it to forward a political agenda when there are real humans behind those. Whether or not I choose a label that you understand doesn't change who I am as a person.

But each interview is amazing. You really get to know the kids. And I was amazed at how different each teen was — coming from different backgrounds, they're in different states. Can you tell us a little bit about the process of connecting with the teens and their family? And were there any teens that you were hoping to be able to interview but weren't able to?

NL: It was more like identities that felt important to include, that I just didn't get to because of space and capacity. I had to recognize that I'm only one person, and I can't do everything. If I had the capacity to go to 50 states and interview 50 diverse kids of completely different identities, I absolutely would have done that. But also I might die. Because this book was so — I don't want to talk about my feelings here, because they're not really important — but it was emotionally traumatic for me to write seven chapters. I can't imagine doing this with 50 kids — their trauma and my trauma all mixing together. That would be a lot of book, for all of us. So, seven was good.

I would have loved a Mormon story, because I've been reporting on LDS communities for a really long time. I think that the story of queer LDS communities would have been really lovely and important to tell, but I just didn't have time to really find the right person — the best story to put forward. I wanted all of these stories to feel really different from each other, and to speak to a unique experience, and for the person to be in the right place to do this. That just didn't work out in the way I wanted it to for a Mormon story.

We have a Black, biracial kid in the book: Mykah. I love Mykah so much, but I would have loved a second Black story. I felt really good that we have two different kinds of AAPI stories. We have a Muslim Pakistani story and a Japanese Hawaiian story. And I wish we'd gotten to do the same thing with the Black community, because there are so many kinds of stories. There are so many kids with their own experiences and their own perspectives to bring. And it would have been really cool if I got to write 50 chapters, to make space for the multiplicity of ways that people can exist even within certain sub-demographics of the community. And if I got to do a sequel — which sounds amazing, but at the same time I feel like I'd need a couple therapists for that — that definitely would be a major priority of mine, continuing to expand representation as much as possible.

But for these kids, it was a matter of reaching out to my communities and families that I've known for a really long time, “Do you know a family that's Muslim? Do you know a family that's AAPI? Or has this kind of experience?” And not all those things worked out. But when you ask enough people with those kind of things in mind, that helped me be more strategic and intentional about who I'm bringing into the conversation. And ultimately the thing that was most important to me wasn't just that they represent diverse voices, I wanted people who had really interesting stories.

I also needed to have this kind of bond with the families, so I would be able to get that special story out of them. With these seven families, even though sometimes it was complicated and hard, we had that. It took months of searching and reaching out and talking to different families, but I feel like I made the right choices. When I look back at this, there's nothing I would do differently.

KS: Were there any barriers that you had to, you know, navigate as you tried to connect with these families, or that kept you from connecting with other families?

NL: Early on, I wasn't sure what the parameters were going to be for the book. I tried to interview younger children, and I just found that they couldn't narrativize their experiences as much. They couldn't speak as much about their own experiences and really reflect on them at 9 years old. I don't know when that happens — that ability to self-reflect — but I noticed that wasn't quite there yet, and I wanted these kids to be able to think about their own experience. So that was definitely a barrier, figuring out what are the right age groups for this, who can really speak to their own experiences rather than their parents.

Then, just connecting people with people can be really hard. With these kids, you have two weeks to connect with each other and come up with something special. With some of the young people, that was harder because they didn't want to do this as much. It was really important to me that for each family, the parents said “yes” and the kids said “yes,” but I would find out later that the reason that the kid wanted it was more to appease their parents than to do it for themselves. Because of that, you have more walls to break through. For the girl from my last chapter, Kylie, it was several days of discussion before I felt like we were really able to just like open up to each other. Summer was about to start. She didn't want to be here. She didn't want to do this. She wanted to be hanging out with her friends at the mall.

And I sort of built into that interview process — we went to batting cages, I took her to a movie, we went to buy her jeans at the mall. That way it felt like she was still getting those young people experiences. It was a reminder for me that not every kid wants to be an activist. It's amazing if you want to do activism and advocacy, we definitely need as many people fighting as possible. But I think being a trans person is about freedom, and about the liberty to live your own life. And I think that freedom and that liberty also applies to opting out. To not wanting to deal with this, to just being your own person, to not being politically engaged. Everybody should have that right. And I hope those kids who don't see themselves as activists felt respected by the book. And if you're reading it, and you have that kind of experience, I hope you feel invited into the space in some way.

KS: You talked about how some of the kids didn't want to be activists, which makes me think of the flow of the book. When I think of trans teens, I tend to think of all the barriers they have in their life. When I started reading your book, the first two stories are very uplifting and positive. That should be wonderful, but as I was reading it, I was thinking, “I can't give this to my son's trans boyfriend, because this is not his lived experience.” Now, it's not all that way. You do go into the struggles, but talk a bit about why it was important to start with such positive experiences — teens who are really able to be themselves — before you really sort of go into some of the harsher struggles trans teens face.

NL: What's funny is it wasn't intentional at all. I was so at the mercy of these family schedules that I even write in the book that I couldn't plan anything over the holidays because all these families were really busy. They've got Halloween, they've got Thanksgiving, they've got Christmas — They can't have me in their house. They don't want me there! March worked for one family. April worked for this family. February worked for this family. It ended up working out. I was very much driven by what they needed and what was good for them, and it worked out in a way that I think was really beneficial for the book.

What I think is cool — and what you're hitting on here — is that the book gets more and more complex with each chapter. In the beginning, there's Wyatt, a kid in South Dakota, who is just a lovely boy, who's so deep and sensitive, and has this sweet poet soul, and has been incredibly loved and affirmed by his family. They have such a lovely story, but it does have harshness and sadness to it, in that they had to leave their church. They've lost a lot of their friends. For some people who are coming into the book, it's the kind of story you may have heard before, or one you might expect. And from there, each chapter just keeps building on that.

One of my favorite things that I got to include in the book was in the second to last chapter — the Florida chapter. There was a scene in the book where I get to hang out on an apartment balcony with Jack — one of the two trans kids that I was profiling there — and she just smoked a cigarette while we talked about Kierkegaard. It was so random, us having this two-hour discussion about arcane philosophy. But I was like, “This HAS to go in the book,” because I — as somebody who reads and consumes culture — have never seen in any piece of media, a scene in which a trans kid gets to have those kinds of conversations that have nothing to do with being trans. It just felt cool because it was, again, recentering this person. You know, Jack, as a whole person who has thoughts and ideas and feelings that are not related to her transness.

If we're gonna have a book that's celebrating trans teenagers, it should really be just a book about teens. I wanted more than anything to reconnect with that experience — the experiences kids have been having for generations. I want Annette Funicello — if she were still alive — to pick up this book, and be like, “I recognize that as being a teen experience.”

KS: That was one of the things that certainly came across to me as I was reading each of these stories. They were teenagers no different than the teenagers in my house, other than maybe some cultural differences. As you were getting to know these teens, you also were able to interview their families. What motivated you to include some of the family stories rather than just focusing on the teens themselves?

NL: I feel like the parent stories are really important, but they shouldn't be the primary focus. I've been reporting on the lives of trans kids for a really long time. And through that work I'm almost always talking to parents, because either their kids are quite young or their kids don't want to be dealing with this. Or their kids are just trying to be safe — a lot of their kids might not be totally out in their community, or if they are, their parents are worried about them being trolled by right-wing nut-jobs on the Internet. Because if you put yourselves out there in an article in the Huffington Post that might feel really good and really validating, but it can come with risks and consequences. You have families that are doxed or that have to move out of their homes, just because they chose to be visible. Not everybody is in a position where they can take that risk, or they just don't want to.

So you have so many situations where the kid can't be that involved with the story, and I understand that. But I always thought that there was a component missing when you're missing the kid's voice, because then people can't hear from them. And I think it allows misinformation and rhetoric to flourish a little bit when the people who should be speaking here aren't able to. That's no one's fault, but I do think it then becomes incumbent for me, if I have the opportunity, to put the voices of trans kids themselves at the center of the discussion, to hear directly from them, and to make sure that they're the ones leading the conversation.

But I do think that the parents are important. Parents are going to be picking this book up. They're going to be curious about the experiences of these kids (who might be like their kids). I want them to make those connections, and to see their own families’ lives in the lives of these youth; that feels like a really amazing opportunity.

I hope they're also doing the same thing for the parents — seeing what other people did, getting a little bit of advice, or seeing what they can take away from it. Like, “Oh, that's really smart. I'm glad they did that that way. I can do that, too, for my kid who's already come out.” (Or for a kid who hasn't come out yet — you know, you might have a trans kid and not know.)

For other parents, it can just be really normalizing to see that nobody has it all figured out. One of my favorite parent stories to tell is Mykah's mom, because she's a white lesbian — Mykah is Black and biracial — who's raising a Black kid in West Virginia, and there's so much she's still trying to figure out in terms of language, or even getting Mykah's pronouns right. She often doesn't, and then beats herself up for that, and that's a real struggle for her.

I wanted to show people that that's okay, that you don't have to have it all figured out. You don't have to be perfect. She's a really great mom, but she has this idea in her head that she's not. No one is harder on Mykah's mom than she is on herself. I know so many parents are like that, they expect themselves to be like perfect allies and to get everything right all the time. And who among us does? But I think that there's such beauty in letting people be represented, with their imperfections and their flaws. And then to say, “It's okay that you are wherever you are, as long as you're trying.”

KS: It goes back to really showing the humanity of these families. As you're going from interview to interview, were there favorite parts of interviewing families? What were your favorite parts of creating this whole book?

NL: It was a struggle for me to figure out how all of the interviews were going to fit together, because for a book like this you have to do a lot of condensing. You have to just condense things for narrative reasons. You could represent everything the exact way it happened, but then it would make absolutely no sense, because you would be constantly jumping between time and different discussions in different spaces. It felt like a cool challenge to just make sure that all of these interviews, and the things that we're talking about, and the themes that we're bringing up always made sense where they were in the chapter. So much had to be reshuffled and reordered, but it was such a fun, unique challenge to figure out, “Okay, how do you make a clear, concise narrative out of all these incredibly disparate parts?”

I think people have this idea when they read the book, that everything was super linear, that I just had the book in my head, and then I wrote it. That did not happen. I didn't even know what this book was going to be when I went to Wyatt's family to hang out in South Dakota for 3 weeks. I was just chilling with Wyatt in the basement, and just talking about stuff. We were all figuring it out together, and a lot of it was trial and error.

KS: Okay, my final thing is: what's next? Do you have another big project? Are you gonna write another book?

NL: I don't know. I need to get this one out! I'm doing so much promotion on this. I put together this absolutely mental spreadsheet of basically every LGBT group in the country, and every affirming church that I could find in every single state. I'm going to reach out to all of them, and I'm going to tell every single one of them about this book. One of the problems that I know that so many queer authors have is finding an audience, because there's not clear pipelines. Who do they talk to about it? They go to media, and maybe somebody gets back to them. Or maybe they don't. Does BookTok find it? Do people find it organically?

I'm just not willing to take that chance. These kids have already sacrificed so much to be in this book. They deserve to have their stories heard. So I have already started reaching out to all these organizations to be like, “This book's out there. Please support it in whatever way.” And I have to say, the people who have been most enthusiastic about this have been churches. That's neat because so many of the stories are religious stories, so we can complicate these narratives that religion is inherently traumatic, and maybe even push faith traditions to just do more to include queer people. Clearly queer people want to be included. They are already part of these religions and these faith traditions, so just show up for them and support them.

When it comes to what comes after this, I don't know. I'm so tired. I need to write another book to make money, so I'm going to have to put myself out there in some way. But it's so hard to go from a book like this, knowing how much work it was, and how much it was not only for me to take on, but for every single person I worked with.

I have an idea I've been batting around with a friend, but I keep missing our deadlines for conversations, because it's so hard to go back into the boiling pot. When am I going to be ready to do this to myself again? I don't know.

I hope that, not only will I at some point have the energy to do this again, but that people are receptive to it in the industry, because it was really hard to get this book picked up. A book like this hadn't been written before, and people were skeptical. We got rejected by everybody, except for a handful of publishers that really saw the vision and understood why a book like this needed to exist.

I hope that if this book is successful, that it will prove to the industry that they should take a chance on underrepresented voices, or voices they haven't heard before, or voices that there isn't a proven market for. I hope we create these pipelines for people. I hope this is a change moment.

I don't know what's gonna happen when this comes out in October. I'm a little nervous that I might have to move or go into hiding or something, but I really hope it's positive and lovely for everybody involved. I hope it's the celebration that these kids really deserve.

KS: Me too! Well, thank you so much for your time and for writing this amazing book. I can't wait to share it. And as soon as this interview goes live I will be sharing it with my Goshen LGBTQ+ Facebook group to let them know about it.

NL: Well, thank you so much for this. I really appreciate the opportunity to just talk about this book and blather on at you.

KS: Yeah! It was awesome!

NL: It’s been so lovely.

American Teenager: How Trans Kids Are Surviving Hate and Finding Joy in a Turbulent Era by Nico Lang (Abrams Press, 9781419773822, Hardcover Nonfiction, $30) On Sale: 10/8/2024

Find out more about the author on Instagram @queernewsdaily

ABA member stores are invited to use this interview or any others in our series of Q&As with Indies Introduce debut authors in newsletters and social media and in online and in-store promotions. Please let us know if you do.